UNDRIP was adopted by the United Nations (UN) in 2007 after 25 years of persistent advocacy by Indigenous Peoples about the repeated violations of their human rights, as defined in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights. UNDRIP is an eloquent call for recognition of both individual human rights and Indigenous collective rights. While a UN declaration on its own does not have the status of a law, the aspirations of a declaration can influence law and policy in sovereign states like Canada.

Canada officially adopted the Declaration in 2016. In 2019, the Province of British Columbia passed the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. In 2021, Bill C-51 was passed by the Parliament of Canada to plan for the implementation of the Declaration at the federal level.

The implementation of UNDRIP will require spaces for Indigenous Peoples to express their frustrations and alienations and have governments sit back to learn and listen. It’s an opportunity for governments to admit that they need to shift their thinking. But it also requires Indigenous Peoples to really step up because it’s a process, not a magic wand. It requires us to be involved and think about what it means for us.

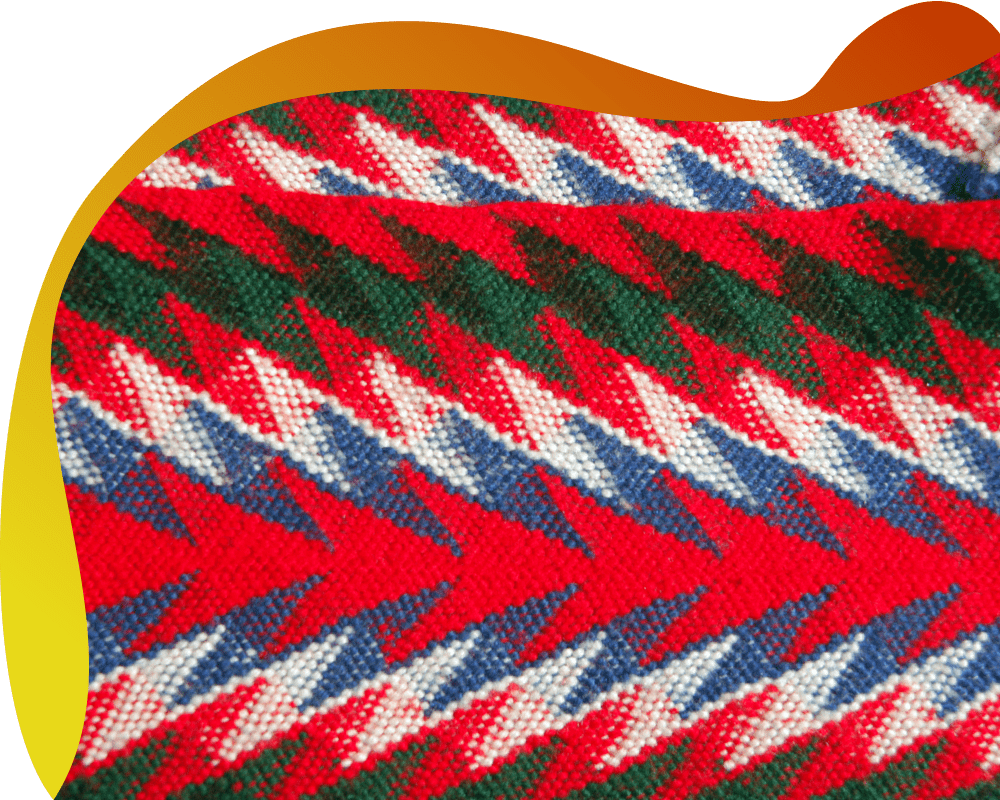

The terms ‘culture,’ ‘traditions,’ ‘expressions,’, ‘arts,’ and ‘languages’ are found in many Articles in the Declaration, which is a strong indication of the importance attached to the rights of Indigenous Peoples to protect and define their identity and heritage collectively. Equally important is the right of Indigenous Peoples to define the meaning of these terms.

See the IHC report Indigenous Heritage and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.